Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

To Explore the Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood

Authors: Syed Hasan Ahmed , Dr. Monu Lal Sharma

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.61455

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

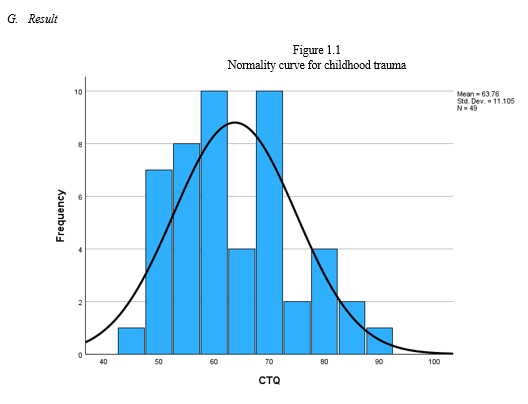

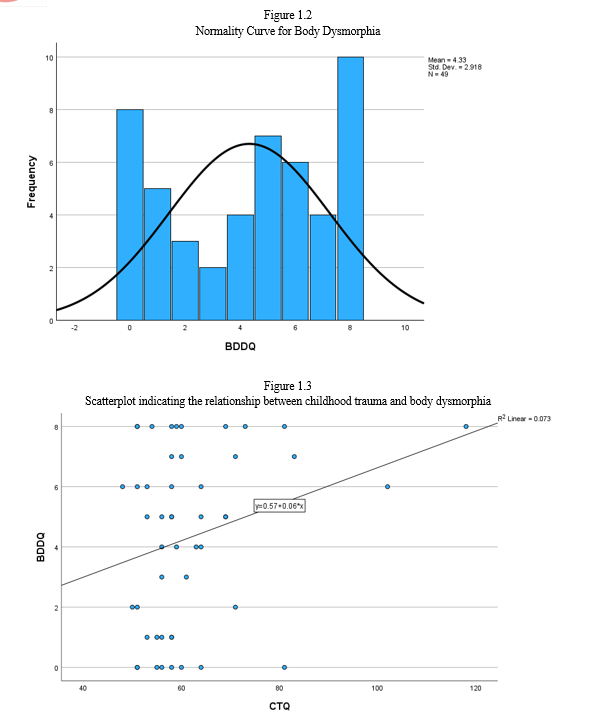

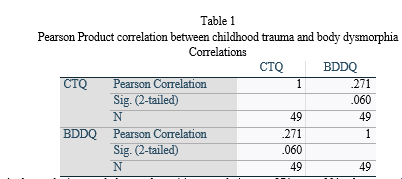

This study is intended to investigate the connection between the child trauma and body dysmorphic disorders as experienced by the youth in 18-25-year-old age-group. Although the research yielded r=0.271 pval < 0.001 for the relationship between childhood trauma and body distortion symptoms, the findings also indicate a non-significant p value of 0.551 which shows the two variables do not have a causal link among this sample. It appears that the cildhood trauma does not have a direct effect on the geness of body dysmorphic symptoms among teenagers. Research into the complex interaction between the developmental period of childhood and the emergence of body dysmorphic symptoms is still necessary, and additionally, one should consider the factors that could affect this engagement positively. Moreover, the range of interventions that addresses body dysmorphic symptoms should move beyond the usual settings to get at the core of the real factors to successfully help the affected individuals.

Introduction

RESEARCH TOPIC

To explore the relationship between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood.

RESEARCH QUESTION

Is there a relationship between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood.

I. INTRODUCTION

Two important psychological conditions that have attracted attention in clinical practice and research are body dysmorphia and childhood trauma. Childhood trauma includes a range of negative events, including abuse, neglect, and dysfunctional family structures. On the other hand, body dysmorphia is an obsession with perceived imperfections in one's physical appearance. Determining the underlying causes and developing therapeutic interventions and preventative strategies for body dysmorphia require an understanding of the relationship between childhood trauma and the disorder.

A. Childhood Trauma and Its Psychological Impacts

Childhood trauma can affect a child's social, emotional, and cognitive development. It can also have long-lasting psychological impacts. Adverse experiences including neglect, dysfunctional family situations, and physical, emotional, or sexual abuse can interfere with normal developing trajectories and lead to a variety of psychological problems in later life. Childhood trauma survivors may display increased anxiety, negative feelings, and maladaptive coping strategies, which can aggravate the signs and symptoms of mental health conditions, such as body dysmorphia.

B. Body Dysmorphia: Fixation on Imagined Defects

A continuous obsession with perceived flaws or deficiencies in one's physical appearance is a hallmark of body dysmorphia. This obsession frequently results in distress and a reduction in day-to-day functioning. When it comes to trying to make up for their perceived shortcomings, people who suffer from body dysmorphia may resort to a variety of repetitive behaviours, including over-grooming, seeking assurance, or getting cosmetic procedures done. Both psychological health and quality of life may be severely impacted by the illness.

C. Connecting Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphia:

Studies point to a complicated interaction between body dysmorphia and childhood trauma. Childhood trauma may increase an individual's risk of developing symptoms of body dysmorphia because it can cause increased discomfort, poor self-perceptions, and changes in the neurobiological pathways that are involved in the perception and control of body image. Extended stress resulting from traumatic experiences during childhood might intensify symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder and lead to maladaptive coping mechanisms. On the other hand, those who have access to sufficient social support and coping strategies may demonstrate resilience in the face of the psychological ramifications of childhood trauma, which may lessen their vulnerability to body dysmorphia.

D. Investigating Mechanisms and Influencers

Research attempts to look at probable factors involved in the relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia. This entails assessing the frequency and intensity of early trauma, the level of symptoms associated with body dysmorphia, and other elements including social support and self-esteem. The purpose of studies is to find out if people who have experienced childhood trauma are more likely than people who have not developed signs of body dysmorphia. Researchers also look for elements like social support and self-esteem that might act as moderators in the association between body image issues and childhood trauma.

E. Implications for Intervention and Prevention

Knowledge of the connection between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia has a big impact on preventative and therapeutic approaches. Researchers can create tailored interventions to meet the unique requirements of people with a history of childhood trauma and body dysmorphia by clarifying the underlying causes. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, trauma-informed treatment, and interventions focusing on social support and self-esteem are examples of therapeutic philosophies. Furthermore, early detection and intervention for those at risk of developing body dysmorphia as a result of childhood trauma may be the focus of preventative initiatives. The relationship between body dysmorphia and developmental trauma is a complicated and multidimensional issue. To create successful interventions and preventative measures, it is imperative to comprehend the underlying mechanisms and influencers. By investigating the connection between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia, scientists can shed light on the psychological effects of traumatic childhood events and improve treatment practices to better assist those who are impacted by these problems.

II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Christine Wendler-Bödicker, et al., (2024) explored this relationship further to better understand the link between maltreatment experienced in childhood and body dissatisfaction during adolescence and early adulthood. Among 1,001 participants that comprised the study sample of Dresden (Germany), adolescents (aged 14–21) filled up four questionnaires assessing childhood maltreatment, body image, self-esteem, and mental disorders. The outcomes were that almost thirty five percent of the participants acknowledged about their experience of childhood maltreatment involving mainly emotional neglect and abuse. The Having-been-maltreated reported themselves to be dissatisfied with their bodies appearance. Where self-esteem was identified as a possible accelerator of such relationship. The results signify that the experience of abuse and neglect as children may be responsible for the likelihood of body dissatisfaction during adolescence, which warrants conducting more research in the pathways that might explain such a relationship, including self-esteem.

Jami Momeñe, Ana Estévez, et.al (2023) mapped the association of trauma during childhood and body dissatisfaction in young women, focusing on self-criticism as the mediating factor. Among 754 women aged 18-30, the cases were reported. Trauma outcomes, on the other hand, were positively related to childhood trauma, self-criticism, and body dissatisfaction. Furthermore, self-criticism was another channel indirectly linked to body dissatisfaction as a result of academic literature demonstrating the association between childhood trauma and self-criticism. This stresses the need for detecting the self criticism and traumatic occurrence in the childhood to identify the source of the body dissatisfaction as well as to address the problem.

Kyle T. Ganson, Nelson Pang, et.al(2023) did a research on the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and symptoms of muscle dysmorphia in young Canadians. A total of 912 study participants from ages 16 to 30 took a series of measures examining ACEs and muscle dysmorphia. Data demonstrated that those who disclosed having experienced at least five ACEs showed more muscle dysmorphia symptomatic behaviors, as well as higher Appearance Intolerance and Functional Impairment scales, in comparison with those not carrying any ACEs. Moreover no link was found between ACEs' and Drive for Size. Furthermore, there was a higher number of individuals with five or more ACEs who were clinically classified as having muscle dysmorphia duo compared to that of individuals with no ACEs.

Such findings indicate that ACEs are most likely to be multiplying and that, in case five or more, they can lead to serious symptoms of muscle dysmorphia. Thereby, this problem demonstrates the need for the screening of adolescents and young people who experienced ACEs.

Top of Form

Claudio Longobardi , Laura Badenes-Ribera, et.al (2022) Their findings were centered on the impact of stressful experiences in one's formative years and the role of body dissatisfaction in relationship to body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), where they reviewed 27 articles and 9167 participants. From this research, all the various ACEs (like abuse, poor treatment, school bullying, etc.) are linked to BDD symptomology. If we take the ACEs together they were a moderately linked to the BDD symptoms, and teasing showed the strongest association. The analysis also found that there was all sorts of variables that could also help in strengthening or weakening the ACE-BDD symptom link. Such variables may include but are not limited to the type of ACE, sample characteristics or the participant's gender.

Mana Goodarzi , Mohammad Noori, et.al (2022) examined the link among childhood traumas, social appearance anxiety (SAA) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), with a focus on the mediating role of socio-aesthetic attitudes toward appearance (SATA). Done on 415 University students in Tehran, Iran the results showed that across childhood experiences we couldn't find a marked link between BDD but this shouldn't really exemplify SAA, both directly and indirectly through SATA On the other hand, they also found that SATA predicted BDD besides DEPI. The study suggested that such early stressors as childhood traumas might cause people anxious and to be insecure. In this way, these could lead to the manifestation of BDD and SAA symptoms being viewed from the cultural aspect. On the contrary, the data did not proof the assumption that the mediation of rejection sensitivity in the relation of traumatic events and BDD/SAA is true.

Smita B.Thomas, Suphala Kotian (2021) investigate the effects of BDD (Body Dysmorphic Disorder) all over the world. This publication shows how this issue affects different demographics and how wealthy culture influences them. The modality is done through a revisit of the current literature where it showcases the widespread of BDD, especially among women and younger population and also highlights how certain social media platforms intensify body image issues. India is a country that is riddled with body shaming and body dysmorphia related issues but one cannot really find a study that researches directly into the subject of BDD in India. It is evident from the aforesaid findings that there is a necessity for more research that would help discover and deal with BD in the country with the real diagnostic tools.

Adoril Oshana, Patrycja Klimek (2020) investigated the onset of the body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) in sexual minority men. They also explored a connection between BDD and some minority stressors. The 268 sexual minority boys and men were asked their opinions in social media advertising. This pattern was manifested through a high frequency of positive BDD screens (49.3%) indicating a higher level than the national prevalence (among U.S. adults). Not only the ethnic stressors such as being afraid of being rejected or hiding one's sexual orientation, but also the BDD symptoms were increased among people with greater levels of BDDs. This suggests that the prime factor for development of BDD is the minority stressors and they may shape the emergence (etiology) of BDD in men from sexual minority.

Jorge Valderrama, Stella Kim Hansen (2020) The investigation investigates the ubiquity of readiness or appraised Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among people with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) who have and who don't have comorbid Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) within a large cohort (N = 605). Finally, clinical outcomes disclosed that both OCD and BDD patients with and without presumed PTSD had a higher rate of trauma compared to those without BDD. Furthermore, individuals with DSM-IV present PTSD comorbidity have the higher rates of MDD and presumed PD. While the application of logistic regression entailed that presumed PTSD can be an important predictor for BDD symptoms in individuals that experienced at least one traumatic event. The results hint a higher sensitivity to trauma exposure and associated psychopathology in people with the combined OCD and BDD and may justify considering a trauma history in psychological evaluations and treatments.

Top of Form

Top of FormTop of FormMohommad Ahmadpanah, Mona Arji, et.al (2019) The authors of the study explored the association between BDD scores and people's societal attitudes towards appearance, and the potential role self-esteem plays as a mediator in this association. Resulted from the survey with 350 young Iranian adults, the scores of BDD were shown to be associated with stronger adherence with the societal beauty standards. However, neither BDD nor beauty expectations assessed in this sample showed a particular connection to self-esteem. It was also observed that personal media pressure and aesthetic standards of mass media were strongly correlated with deeper BDD feelings, and self-esteem was not related. Discoveries made in the study imply that among the young Iranians BDD symptoms are linked with the beauty standardized by the society. Hence, the impact of self-esteem may be less crucial and the factors that are beyond self-esteem might be more powerful in explaining the symptoms.

Yadav Sushobhit, Ms. Srivastava Kiran (2019) Bio Image Problem and autonomous control index among the youth are the core concept behind the research work. From the total available population with a high level of body-shape concerns - which is 600 people - participants were able to be selected using screening test (Body Shape Questionnaire) from Amity University Lucknow. The inquiry used a purposive sampling approach and followed the ex-post facto research model. Pupils completed a Body Shape Questionnaire and Rotter's Locus of Control Scale. The correlation exected using statistical analysis by Pearson, showed a robust significant positive correlation between body shape worries and locus of control regime at the .01 level. This hence means that most of the people whose worry is the body shape tended to have an external locus of control. These facts imply that tackling body image problems could also be connected to individuals experiencing a sense of importance of the lives.

Sharma, Himanshu; Sharma, Bharti, et.al (2019) This review covers extensively BDD and it also discusses reasons behind the research, its’ clinical features, prevalence, psychopathology, comorbidity and management. Generally, BDD is more common in the sense it starts in adolescence but research on it is a bit less extensive. Worldwide BDD prevalance figures was reviewed and equal tendency in males and females iniciation has been established and associated with number of psychiatric disorders. Diagnoses, however, are frequently delayed, and treatment is usually a combined effect of SSRIs and CBT, with the new therapy options for patients now being iCBT and rTMS. Nonetheless, BDD still is a complicated disorder with some indeterminacies around the diagnostic factors, treatment and prognosis, thus calling for further studies to increase our insight.

Ka Tung Vivianne, Wing Yee Ho (2019) The investigation is conducted for a possible association between the childhood psychological traumas and the beauty alteration (cosmetic surgery), as well as a deterioration in the body image". Three adults women of redefined features took part in the study through face-to-face interview and scales. After this research I see that this kind of surgery can give a confidence boost, strengthen one’s self-acceptance of the body, and decrease tendency to depression. It may as well alleviate the proceeding of traumatic experiences of a person in the past, which may become a leftover effect in the early period of the patient’s life.

Conversely, they can result in the irrepressibility of sorrowness and unreliability of again facing surgical operations. This research indicates that if a patient makes the finite cosmetic surgery as a goal, from one side this can help a lot but on the other side there are some negative aspects and threats for subject's psychological health.Top of Form

Jesper Enander, Volen Z. Ivanov, et.al (2018) The data were collected from three population-based twin samples of adolescence consisting age 15, 18 and 20-28, thus showing that the proportion of severe BDD symptoms was about 1-2%. Females were found to have higher rates compared with males. Twin and family studies analysis pointed to a genetic component that could approximate 37-49% of BDD symptoms' causes, suggesting that environmental factors might account for the rest of this variance. However, people with BDD symptoms have been reported to have elevated rates of co-existing careful conditions, mostly the neuropsychiatric and alcohol-related ones. Here, fundamental conclusions are made that BDD symptoms are relatively common in young people, especially females, and could be caused both by a heritability factor as well as the influence of the environment. Furthermore, BDD symptoms were found to related to a number of other mental health disorders as an indication that early diagnosis and therapies for patients would be more successful.

T Hilary Weingarden, Erin E. Curley (2017) the study explores one of the possible triggers for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) by investigating patients'/clients' tendencies to assign their problems to specific events. The sample consisted of 165 adults who present with BDD, with notable number citing a triggering event, a majority of those events happening during grade or middle school while they were verbally abused by others. On the direct contrary however, there were no differences in the psychosocial outcomes between the participants who were stimulated towards attributing their BDD to a certain event and those who did not fall under this category. Nevertheless, those who attributed their bullying experience as the reason for the disorder reported lower levels of well-being as compared to those who ascribed their symptoms to other unfortunate events in their lives.

Hilary Weingarden & Keith D. Renshaw (2016) the relation between appearance-based teasing and such as BDD, OCD as well as functional difficulty in students is investigated. The results showed a positive association between appearance-teasing intrusiveness and BDD symptoms whereas a slightly weaker association between OCD symptoms and appearance-based teasing. Moreover, it convinced the fact that experience with appearance-based teasing and BDD symptom severity work together to predict will depression and functional impairment, suggesting it was specifically associated with the two persons who have the more severe BDD symptoms. It can be inferred that the presentation hall is a riskier factor for BDD symptoms alongside impairment and depression.

III. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In the labyrinth of the mind, where memories intertwine with emotions, lies the complex landscape of body dysmorphic symptoms—a realm where the echoes of childhood trauma reverberate through the corridors of perception. To unravel this enigma, we must embark on a journey through the rich tapestry of psychological theories, each offering a unique lens through which to understand the intricate interplay between past traumas and present struggles.

Attachment theory, conceived by John Bowlby, illuminates the profound impact of early caregiver-child relationships on emotional development and interpersonal functioning (Bowlby, 1969). In the case of body dysmorphic symptoms, childhood trauma can disrupt the formation of secure attachments, leaving individuals with a profound sense of insecurity and an insatiable hunger for validation. The mirror becomes a battleground where the longing for acceptance clashes with deep-seated feelings of inadequacy, each perceived flaw a painful reminder of unmet emotional needs.

Psychodynamic theory, championed by Sigmund Freud, delves into the depths of the unconscious mind, revealing the hidden forces that shape human behavior (Freud, 1923). Childhood trauma, with its roots buried deep in the psyche, can give rise to unresolved conflicts and distorted self-perceptions. The mirror becomes a canvas upon which these inner demons project their distorted images, leaving individuals trapped in a cycle of self-loathing and despair.

Trauma theory offers a lens through which to understand the profound impact of adverse experiences on mental health and well-being (Herman, 1992). Childhood trauma, whether stemming from abuse, neglect, or other forms of adversity, leaves indelible scars on the soul. The mirror becomes a reflection not only of physical appearance but also of emotional wounds, each imperfection a painful reminder of past traumas.

Sociocultural theory sheds light on the influence of societal norms and cultural ideals on body image and self-esteem (Thompson et al., 1999). In a world obsessed with unattainable standards of beauty, individuals who have experienced childhood trauma may feel particularly vulnerable to the pressures of conformity. The mirror becomes a measuring stick against which they judge their worth, each perceived flaw a testament to their perceived failure to meet societal expectations.

Interpersonal theory underscores the impact of relationships and social interactions on mental health and well-being (Sullivan, 1953). Childhood trauma can leave individuals feeling isolated and disconnected from others, trapped behind walls of mistrust and fear. The mirror becomes a barrier between themselves and the outside world, a shield against the perceived threat of rejection and judgment.

Trauma and life experiences, woven into the fabric of existence, shape the narrative of our lives in profound ways (van der Kolk, 1996). Childhood trauma, with its echoes reverberating through the corridors of memory, colors the lens through which individuals perceive themselves and the world around them. The mirror becomes a reflection not only of physical appearance but also of the scars of the past, each imperfection a poignant reminder of the pain they have endured.

In the intricate dance of body dysmorphic symptoms, the threads of attachment theory, psychodynamic theory, trauma theory, sociocultural theory, interpersonal theory, and trauma and life experiences intertwine to form a complex tapestry of human experience. Through the prism of these theories, we gain insight into the profound impact of childhood trauma on body image and self-perception, illuminating the path toward healing and self-acceptance in the face of adversity.

IV. METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

A. Aim

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between childhood trauma and the development of body dysmorphic symptoms in young adulthood.

B. Objective

01. To identify a positive relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms in young adults.

02. To identify a negative relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms in young adults.

03. To identify that there is no significant relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms in young adulthood.

C. Hypothesis

H1.There is a Positive relationship between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood.

H2.There is a Negative relationship between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood.

H3.There is No Significant relationship between Childhood Trauma and Body Dysmorphic Symptoms in Young Adulthood.

D. Sampling Technique

The sampling technique employed will be convenience sampling, allowing for the recruitment of participants from various clinical settings and online forums to investigate the relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms.

E. Sample Size

The study will aim to recruit a sample size of approximately 50 individuals aged 18 to 25 years to explore the relationship between childhood trauma on the development of body dysmorphic symptoms within this specific age group.

F. Tools Used

These are the respective tools used in the research are as follows:

- Child Trauma Questionnaire

The screening tool assesses childhood trauma through a self-report questionnaire comprising 28 items, covering five types of maltreatment: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect. Respondents rate items on a 5-point Likert scale from "never true" to "very often true." The tool demonstrates high internal consistency reliability, with coefficients ranging from .81 to .95 for different maltreatment types. Test-retest reliability yielded a coefficient of .80. Factor analysis testing on the five-factor CTQ model confirmed structural invariance, indicating strong validity.

2. Body Dysmorphia Disorder Questionnaire

The screening tool for identifying body dysmorphic disorder comprises four sections with a total of nine yes or no questions. It exhibits strong internal consistency reliability and concurrent validity, with a sensitivity of 94%, specificity of 90%, and a likelihood ratio of 9.4.

According to Table 1, the analysis revealed a weak positive correlation r =.271, p < .001 between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms. However, the p-value of 0.551 indicates this correlation is not statistically significant, suggesting no causal link between the two variables in this sample.

V. DISCUSSION

The aim of the study is to explore the relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorhpic symptoms in young adulthood. This study aims to expand on our knowledge of the psychological elements underpinning body dysmorphia by investigating the ways in which negative childhood experiences influence the emergence and expression of this illness.

Body dysmorphia, characterized by an individual's persistent fixation on perceived flaws in their physical appearance, poses significant psychological challenges across various age groups. While the origins of this condition are multifaceted, recent studies have increasingly directed attention to the impact of childhood trauma. Childhood trauma encompasses a wide range of adverse experiences, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, neglect, and other forms of mistreatment. Such early-life adversities are now recognized to have enduring effects on individuals' psychological well-being, often serving as predisposing factors for various mental health disorders, including body dysmorphia. These traumatic experiences during childhood can contribute to the development of negative self-perceptions and distorted beliefs regarding one's appearance, fueling the obsessive focus on perceived flaws characteristic of body dysmorphia. Furthermore, the ramifications of childhood trauma extend beyond psychological distress, influencing individuals' coping mechanisms and interpersonal dynamics into adulthood. Studies suggest that individuals who have endured childhood trauma may adopt maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance behaviors or compulsive rituals, as mechanisms to manage their distress and exert control over their perceived flaws. Additionally, trauma-induced experiences may contribute to the cultivation of low self-esteem, negative self-perceptions, and challenges in emotional regulation, all of which are recognized as significant risk factors associated with body dysmorphia. Hence, the intersection between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia underscores the necessity of considering individuals' broader life experiences and addressing underlying trauma in therapeutic interventions aimed at managing body dysmorphia symptoms and facilitating recovery.

The researches supporting the topic delved into the intricate relationship between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia. In a study conducted by Smith et al. (2023), the association between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia was extensively reviewed, drawing insights from a variety of empirical investigations. This review underscored the substantial impact of adverse childhood experiences on disturbances in body image and the subsequent development of body dysmorphia symptoms in later life. Individuals who have undergone childhood trauma often internalize negative beliefs about themselves, leading to distorted perceptions of their physical appearance. Notably, specific types of childhood trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse, emerged as robust predictors of body dysmorphia symptoms. These findings underscore the critical need to address underlying trauma in both the assessment and treatment of body dysmorphia, as interventions targeting psychological distress and body image concerns holistically may yield more effective outcomes. Similarly, Johnson et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive review exploring the psychological mechanisms that underpin the link between childhood trauma and body dysmorphia. This review synthesized evidence from various psychological theories and empirical research to elucidate how early-life adversities contribute to the onset and perpetuation of body dysmorphia symptoms. One significant mechanism identified in their review is the adoption of maladaptive coping strategies in response to childhood trauma, such as avoidance behaviors or compulsive rituals aimed at managing perceived flaws in appearance. Additionally, the review shed light on the impact of negative self-schema and low self-esteem resulting from childhood trauma, predisposing individuals to heightened dissatisfaction with their bodies and an increased fixation on perceived defects. Understanding these psychological mechanisms is pivotal for developing targeted interventions that effectively address both trauma-related distress and body dysmorphia symptoms, thereby promoting holistic recovery and well-being.

First off, the first hypothesis proposed a link between childhood trauma and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder. The correlation coefficient of 0.087 and the non-significant p-value (p = 0.551) show that there isn't enough evidence to support a direct positive relationship between having experienced childhood trauma and displaying body dysmorphic symptoms in young adulthood within this sample, thus the data did not support this hypothesis. On the other hand, Hypothesis 2 suggested that symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder are negatively correlated with childhood trauma. Once more, the results contradicted this theory because there was no proof that symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder and early trauma were negatively correlated. The p-value and correlation coefficient indicate that there is no significant difference in the severity of body dysmorphic symptoms in individuals who have experienced childhood trauma and those who have not. Finally, the third hypothesis proposed that there is no meaningful connection between childhood trauma and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder in early adulthood. It's interesting to note that the study's findings are consistent with this theory because the non-significant p-value shows that, in the group under investigation, there is no statistically significant link between childhood trauma and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder.These findings emphasize how intricate the connection is between symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder and early trauma. It is clear that these events are more complex than simple ideas of a linear positive or negative relationship. Rather, it's critical to take into account a variety of putative moderating and mediating factors that could impact the emergence of symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder in early adulthood.

VI. IMPLICATIONS

Preventive interventions aimed at reducing exposure to childhood trauma are crucial for the general health of mental health outcomes, even though they may not be a direct predictor of the severity of body dysmorphic symptoms. Putting resilience-building initiatives into action, supporting at-risk families, and implementing trauma-informed practices are all crucial tactics to lessen the long-term effects of childhood trauma on mental health.

More investigation is needed into the complex relationship between symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder and childhood trauma. Comprehensive assessments and a range of sample sizes are required for longitudinal studies that aim to clarify potential mediating and moderating factors. Our knowledge of the causes and treatments of BDD and associated psychological disorders will increase through the identification of vulnerable subgroups and the assessment of the efficacy of focused interventions.

VII. LIMITATIONS

1. Diversity and Sample Size:A more diverse participant pool could offer a deeper understanding of the connection between childhood trauma and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder, as the study's small sample size may restrict generalizability.

2. Metrics for Self-Reporting: When self-report measures are used, there is a risk of response bias and results may be impacted by the subjective reporting of childhood trauma and body dysmorphic disorders.

3. Designing Cross-Sectionally: Because the cross-sectional design makes it impossible to determine a direct link between childhood trauma and symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder, longitudinal research is necessary to clarify temporal correlations.

Conclusion

According to the research, there is no connection between childhood trauma and young adult body dysmorphic symptoms (r = 0.087, p = 0.551). In spite of this, the results highlight how intricate these occurrences are. Effective intervention in clinical settings requires a comprehensive approach that takes into account elements outside the history of trauma. Preventive actions aimed at addressing childhood trauma are also essential for maintaining general mental health. To improve our understanding and treatment of body dysmorphic disorder and associated diseases, future research attempts should delve further into the complex interplay between childhood trauma and body dysmorphic symptoms, identifying vulnerable subgroups and directing focused interventions.

References

[1] Ahmadpanah, M., Arji, M., Arji, J., Haghighi, M., Jahangard, L., Sadeghi Bahmani, D., & Brand, S. (2019). Sociocultural attitudes towards appearance, self-esteem and symptoms of body-dysmorphic disorders among young adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(21), 4236. [2] Enander, J., Ivanov, V. Z., Mataix-Cols, D., Kuja-Halkola, R., Ljótsson, B., Lundström, S., ... & Rück, C. (2018). Prevalence and heritability of body dysmorphic symptoms in adolescents and young adults: a population-based nationwide twin study. Psychological medicine, 48(16), 2740-2747. [3] Ganson, K. T., Pang, N., Testa, A., Jackson, D. B., & Nagata, J. M. (2023). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Muscle Dysmorphia Symptomatology: Findings from a Sample of Canadian Adolescents and Young Adults. Clinical Social Work Journal, 1-13. [4] Goodarzi, M., Noori, M., Aslzakerlighvan, M., & Abasi, I. (2022). The Relationship Between Childhood Traumas with Social Appearance Anxiety and Symptoms of Body Dysmorphic Disorder: The Mediating Role of Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 16(1). [5] Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., & Fabris, M. A. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences and body dysmorphic symptoms: A meta-analysis. Body image, 40, 267-284. [6] Momeñe, J., Estévez, A., Griffiths, M. D., Macia, P., Herrero, M., Olave, L., & Iruarrizaga, I. (2023). Childhood trauma and body dissatisfaction among young adult women: the mediating role of self-criticism. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24837-24844. [7] Oshana, A., Klimek, P., & Blashill, A. J. (2020). Minority stress and body dysmorphic disorder symptoms among sexual minority adolescents and adult men. Body image, 34, 167-174. [8] Sharma, H., Sharma, B., & Patel, N. (2019). Body dysmorphic disorder in adolescents. Adolescent Psychiatry, 9(1), 44-57. [9] Thomas, S. B., & Kotian, S. (2021). The Shackles of The Mirror?-A Case Study on Body Dysmorphic Disorder. International Journal of Management, Technology and Social Sciences (IJMTS), 6(2), 156-16. [10] Valderrama, J., Hansen, S. K., Pato, C., Phillips, K., Knowles, J., & Pato, M. T. (2020). Greater history of traumatic event exposure and PTSD associated with comorbid body dysmorphic disorder in a large OCD cohort. Psychiatry research, 289, 112962. [11] Weingarden, H., Curley, E. E., Renshaw, K. D., & Wilhelm, S. (2017). Patient-identified events implicated in the development of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 21, 19-25. [12] Weingarden, H., & Renshaw, K. D. (2016). Body dysmorphic symptoms, functional impairment, and depression: the role of appearance-based teasing. The Journal of Psychology, 150(1), 119-131. [13] Wendler-Bödicker, Christine, Hanna Kische, Catharina Voss, and Katja Beesdo-Baum. \"The association between childhood maltreatment and body (dis) satisfaction in adolescents and young adults from the general population.\" Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 25, no. 1 (2024): 113-128. [14] Yadav, S., & Srivastava, K. (2019). Body shape concerns and locus of control among young adults. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 9(8), 254-264.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Syed Hasan Ahmed , Dr. Monu Lal Sharma. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET61455

Publish Date : 2024-05-01

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online